If you’ve ever worked with distributed databases, you’ve probably heard the phrase “CAP theorem: Pick two.” It’s one of those principles that sounds simple but drives the design of almost every distributed system we use today. In this post, I’ll break down what it really means, how different database systems fit into it, and why configuration choices can sometimes push a system from one category to another.

The core idea behind CAP

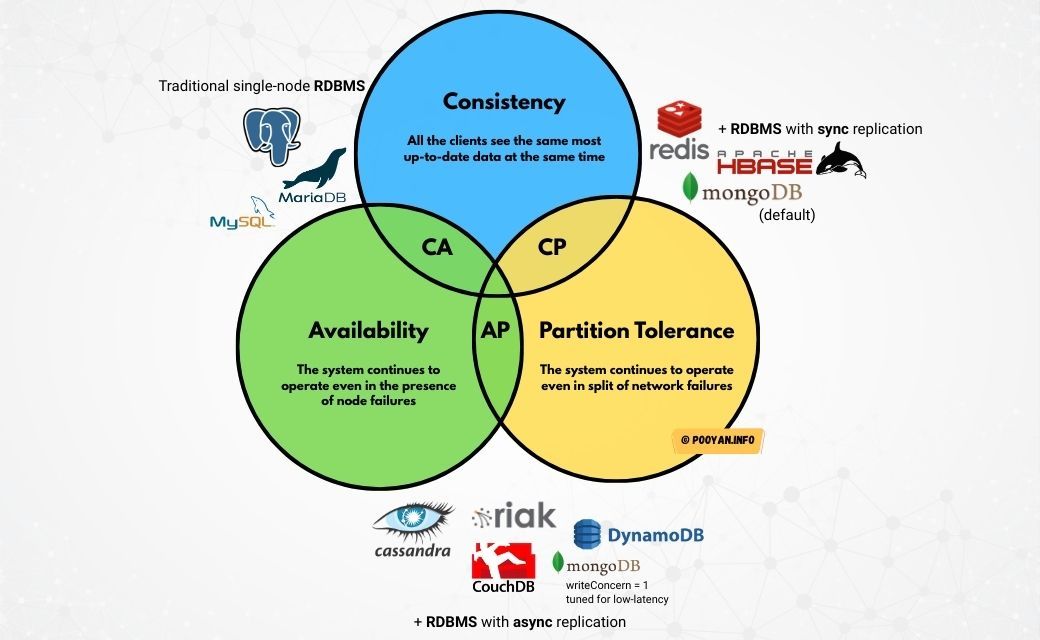

The CAP theorem says that in a distributed system, when a network partition happens, you can guarantee only two of the following:

— Consistency (C): every read sees the latest successful write (or you get an error).

— Availability (A): every request gets a non-error response, even if the data is stale.

— Partition tolerance (P): the system keeps working even when parts of the network can’t talk to each other.

Since partitions do happen, real systems pick between C and A during a split^1.

How databases map to CAP

— CA (Consistency + Availability): works only if we assume no partitions. A single-node PostgreSQL or MySQL database is CA — once you distribute it, you can’t keep both C and A during a split.

— CP (Consistency + Partition tolerance): systems that pause writes if they can’t guarantee a consistent state. Think Google Spanner^5, CockroachDB, and HBase. They use consensus or quorum, so if the majority isn’t available, writes stop until it’s safe to continue.

— AP (Availability + Partition tolerance): systems that stay available and reconcile later (eventual consistency). Examples: Cassandra, Amazon DynamoDB^4 (eventual consistency by default with an option for strong reads).

RDBMS can be CA, CP, or AP depending on setup

This often causes confusion because many people think all relational databases are CA. In reality:

— A single-node RDBMS like PostgreSQL or MySQL is CA because there’s no partition to handle.

— With synchronous replication, if a partition prevents quorum, writes stop → CP behavior.

— With asynchronous replication, writes continue even if replicas lag → AP-leaning behavior (you risk stale reads or rollbacks).

So the same database engine can behave differently depending on replication mode and topology.

Why MongoDB is CP by default

By default, MongoDB writes wait for a majority of replicas to acknowledge and reads go to the primary. If the primary loses majority, writes pause until a new primary is elected — so consistency wins over availability^2.

But this is configurable. If you set writeConcern: 1 and read from secondaries, you get lower latency and

higher availability, at the cost of possibly stale data^3.

Topology also affects CAP

— Single leader + synchronous replicas: losing quorum → reject writes (CP behavior).

— Single leader + asynchronous replicas: keep accepting writes but risk stale reads/rollbacks (AP-leaning).

— Quorum/consensus multi-replica (Raft/Paxos): majority required; without it, systems pause to stay consistent (CP). A good reference is Google Spanner with its external consistency and TrueTime API^5.

Coordination systems behave like CP

Tools like ZooKeeper or etcd, even though they are not databases, store small amounts of metadata for leader election or distributed locks. They’d rather stop progress than risk a split-brain state, so they behave like CP systems^6.

Beyond CAP: latency vs. consistency

Even when the network is healthy, many systems offer a choice between lower latency and stronger consistency. This is captured by the PACELC theorem^7.

For example, DynamoDB lets you choose between eventually consistent reads (faster) and strongly consistent reads (slower)^4.

Quick rules of thumb

— Financial systems, inventory, ledgers: pick CP — pause writes rather than risk inconsistency.

— Feeds, metrics, product catalogs: pick AP — stay available, reconcile later.

— Mixed needs: use tunable consistency per operation (e.g., strong reads in DynamoDB, majority writes in MongoDB).

References

4 AWS: DynamoDB Read Consistency