Open Source License Auditor

To increase the agility of our development, we usually first search Github or any package manager we know to see if we can use an available package already built to do the job. This increases the velocity of technical teams, but as CTO or a technical manager, should I allow everyone to add any package they find on the internet?

Adding a package from a random "unknown developer" not only can potentially increase security risks but also can bring serious legal consequences for companies.

For example, if you have private repositories with potential Intellectual Properties (IP) in them that you want to protect, not only should you avoid using copyrighted material without permission, but also you should stop using OSS licenses that potentially can force you to open source the whole project or spend a lot of time and money to remove them later on.

To be more precise, when you incorporate GPL-licensed code into your company's codebase and distribute the resulting software internally or externally, you must ensure that the entire combined work is made available under the GPL or a compatible license. This means you must provide recipients with the corresponding source code, allowing them to modify and distribute it.

Also, the GPL requires you to give up Intellectual Property (IP) and disclose and make the source code of the combined work available to anyone who receives the software. This includes the GPL-licensed package and your own code that interfaces or links with it. You must provide the source code alongside the distributed software or make it easily accessible.

Has any business been affected so far?

There have been instances where companies have faced legal challenges or controversies related to the use of open-source licenses, and here are some notable examples where companies faced legal pressure or disputes on open-source licensing:

VMware vs. Christoph Hellwig (2006-2016):

As stated in the Conservancy Announces Funding for GPL Compliance Lawsuit article, the Christoph Hellwig Continues VMware GPL Enforcement Suit in Germany article, and the VMware is hit by lawsuit contending GPL violation article, Christoph Hellwig, a Linux kernel developer, sued VMware for allegedly incorporating his code into their proprietary ESXi hypervisor product without complying with the GPL. The lawsuit aimed to enforce compliance with the GPL and make VMware release the source code of the entire product. The case eventually settled, with VMware having announced to discontinue the use of Linux code in their hypervisor in the future and agreeing to comply with the GPL.

BusyBox lawsuits:

BusyBox is a set of Unix utilities released under the GPLv2. Several lawsuits have been filed against companies for incorporating BusyBox into their products but failing to comply with the GPL requirements. Some notable cases include:

Monsoon Multimedia (2007):

Monsoon Multimedia was sued by the Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC) for distributing BusyBox without providing the source code. The case settled, resulting in Monsoon Multimedia agreeing to comply with the GPL and releasing the source code.

Verizon Communications (2007):

SFLC filed a lawsuit against Verizon for distributing BusyBox in their FiOS router without releasing the source code. The case settled with Verizon agreeing to comply with the GPL and release the source code.

Westinghouse Digital (2008):

Westinghouse Digital was sued by SFLC for not providing the source code of BusyBox included in their products. The case settled with Westinghouse Digital agreeing to comply with the GPL and release the source code. On about August 3, 2010, BusyBox won from Westinghouse a default judgment of triple damages of $90,000 and lawyers' costs and fees of $47,865, and possession of "presumably a lot of high-def TVs" as infringing equipment in the lawsuit Software Freedom Conservancy v. Best Buy, et al., the GPL infringement case noted in the paragraph above.

Some examples of potentially dangerous licenses

When it comes to open-source software licenses, it is essential to note that different licenses have different terms and conditions. While considering a license "dangerous" is subjective, some licenses may have provisions that could create challenges or conflicts in specific scenarios. Here are a few examples of open-source licenses that some individuals or organizations may consider to have potentially challenging aspects:

GNU General Public License (GPL):

The GPL is a copyleft license that ensures the software's freedom and requires that derivative works be distributed under the same GPL terms. Some companies may find the copyleft aspect of the GPL restrictive because it mandates that the entire combined work be made available under the GPL when distributed. This can pose challenges if you have proprietary or closed-source components in your software that you do not want to open source.

Affero General Public License (AGPL):

The AGPL is a variant of the GPL that specifically covers network-based software applications. It extends the copyleft obligations of the GPL to software accessed over a network. That means if you modify and use AGPL-licensed software on a server and allow users to interact with it over a network, you must make the source code available to those users. This can be seen as potentially onerous for companies that provide software-as-a-service (SaaS) or web-based applications.

Reciprocal Public License (RPL):

The RPL is a license that requires any software that uses RPL-licensed code to be made available under the RPL or a compatible license. It has strict reciprocity requirements that some organizations may perceive as overly restrictive.

Cryptographic Autonomy License (CAL):

The CAL is a license designed to protect users' autonomy in cryptographic software systems. It includes requirements such as key disclosure and limitations on denial of service to ensure user freedom. While the CAL is relatively new and its adoption is still limited, some organizations may find its provisions challenging or potentially limiting.

Commons Clause:

While not technically an open-source license, the Commons Clause is a license addendum that can be applied to open-source software. It restricts specific commercial uses of the software, which may conflict with open-source principles. The Commons Clause has generated debates and controversies within the open-source community due to its departure from traditional open-source licensing principles.

How to reduce the risk?

You can add tools to audit all your dependencies, check licenses they use, and alert you if there is a potential risk or better to block developers from adding the problematic dependency to your main branch.

One of the tools you can be used is an open-source project called oss-license-auditor (olAudit). If you use Github Action, you can use this Action.

Please note that all the package manager lock files should exist and be committed to your repository. If you are not sure why this is important, please read this article. Additionally, if you use NPM, you can read this article.

How to use olAudit Github Action

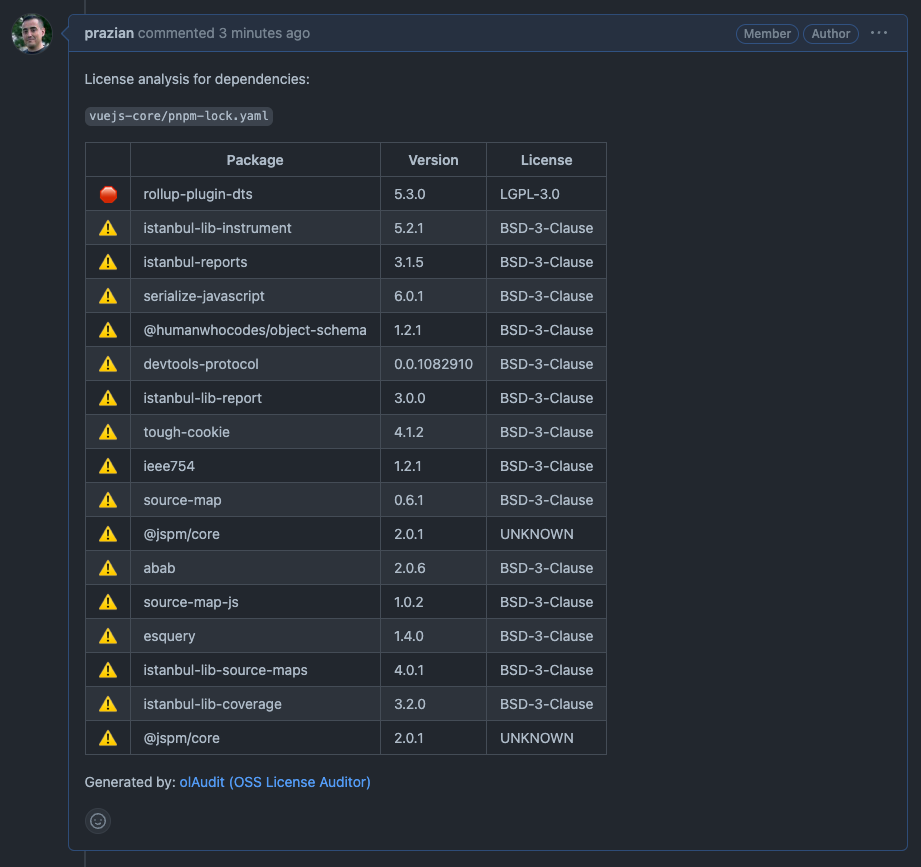

You can use olAudit Github Action to check your source code and audit your code dependencies automatically. This tool can comment on PR the complete list of your dependencies or only the problematic ones.

Right now, it supports the following languages and package managers:

Golang (go.mod):

Golang, if go.mod is present.

PNPM (pnpm-lock.yaml)

TypeScript or JavaScript, if pnpm-lock.yaml is present.

NPM (package-lock.json):

TypeScript or JavaScript, if package-lock.json is present.

Yarn (yarn.lock - only NPM)

TypeScript or JavaScript, if yarn.lock is present.

Soon, it supports the following languages and package managers as well:

Yarn (other sources)

PIP (requirements.txt)

PIP (Pipfile.lock)

Composer (composer.lock)

Maven (pom.xml)

Gradle (build.gradle)

Gradle (build.gradle.kts)

Cargo (Cargo.lock - Rust)

Bower (bower.json)

How to use it?

Check out ">olAudit Github Action on Github Marketplace or its source code on this repository. Then follow the instruction there or copy-paste the example from the readme.

For example, if you use Github Action, you can copy/paste this example to test it out:

name: Audit licenses

on: pull_request: branches: master # Update to your branch name

jobs: audit-licenses: runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: OSS License Auditor uses: digi-wolk/olaudit-action@v1 with: path: . comment-on-pr: true only-risky: true github-token: $

If the action is set up to run on Pull Request creation/updates, and if it is set to comment on the PR when a license is detected that needs attention, you will see a message like this:

olAudit: Comment on Github PR

You can check out this repository to dig into how the tool works.

What if I don't use Github Actions?

You can either directly build and run the tool from the main repository, or if you have Docker installed, you can use the Docker image on DockerHub.

For example, you can run this command to scan the code in the current directory:

To use an specific version: (best practice)

docker run --rm -it -v $(pwd):/app prazian/oss-license-audit:v1 -path=.

To use the latest version:

docker run --rm -it -v $(pwd):/app prazian/oss-license-audit:latest -path=.

In the example above:

- $(pwd) means the current directory.

- If you want to scan another directory, replace $(pwd) with the path to that directory you want to scan.

- If you want to scan another directory, replace the dot (current directory) in -path=. with the path to the directory you want to scan.

- Dot in the -path=. means the current directory.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the perception of a license as "dangerous" may vary depending on an organization's specific needs and goals. While some companies might consider certain licenses challenging or restrictive, others may consider them as essential to promoting openness, collaboration, and software sharing. It's crucial to evaluate and understand the terms and requirements of a license before incorporating open-source software into your projects, and consulting legal experts can provide further guidance based on your specific circumstances.

Finally, here are the links to the tool and its source code:

- Marketplace: github.com/marketplace/actions/oss-license-auditor

- Action’s code: github.com/digi-wolk/olaudit-action

- Solution’s code: github.com/digi-wolk/oss-license-auditor

- Docker Image: hub.docker.com/r/prazian/oss-license-audit

Note: Docker image’s URL is subject to change